We will be closed September 20th through October 5th. Online orders are still welcome during this period and will be processed beginning October 6. We appreciate your understanding and look forward to serving you upon return.

We will be closed September 20th through October 5th. Online orders are still welcome during this period and will be processed beginning October 6. We appreciate your understanding and look forward to serving you upon return.

I am absolutely blown away! For my 50th Bday, my lovely and sweet wife Annie Wendel commissioned this gorgeous cajon from Kopf Percussion. The body is black walnut and the two faceplates are made in house from bookmatched spalted maple wood. The visual beauty of this instrument is completely matched by the incredible sound. Even the bass port is made of the same walnut as the body. The joinery is impeccable and the attention to detail that Steve demonstrates is second to none. I’m truly blessed to add this beautiful cajon to my collection and I can’t recommend his work more highly! If you’re interested in cajons check out Kopf Percussion!

Use headphones to listen for the best sound.

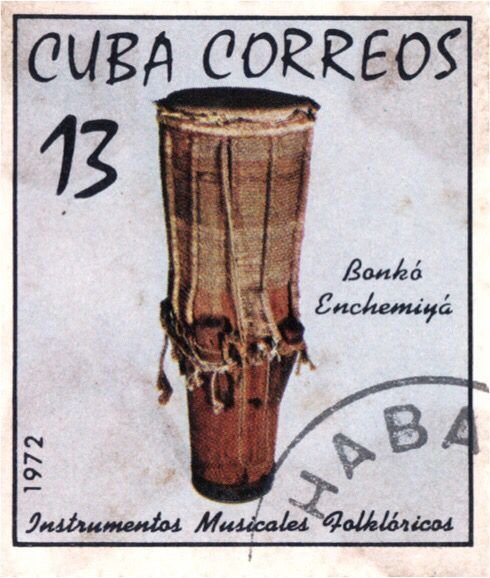

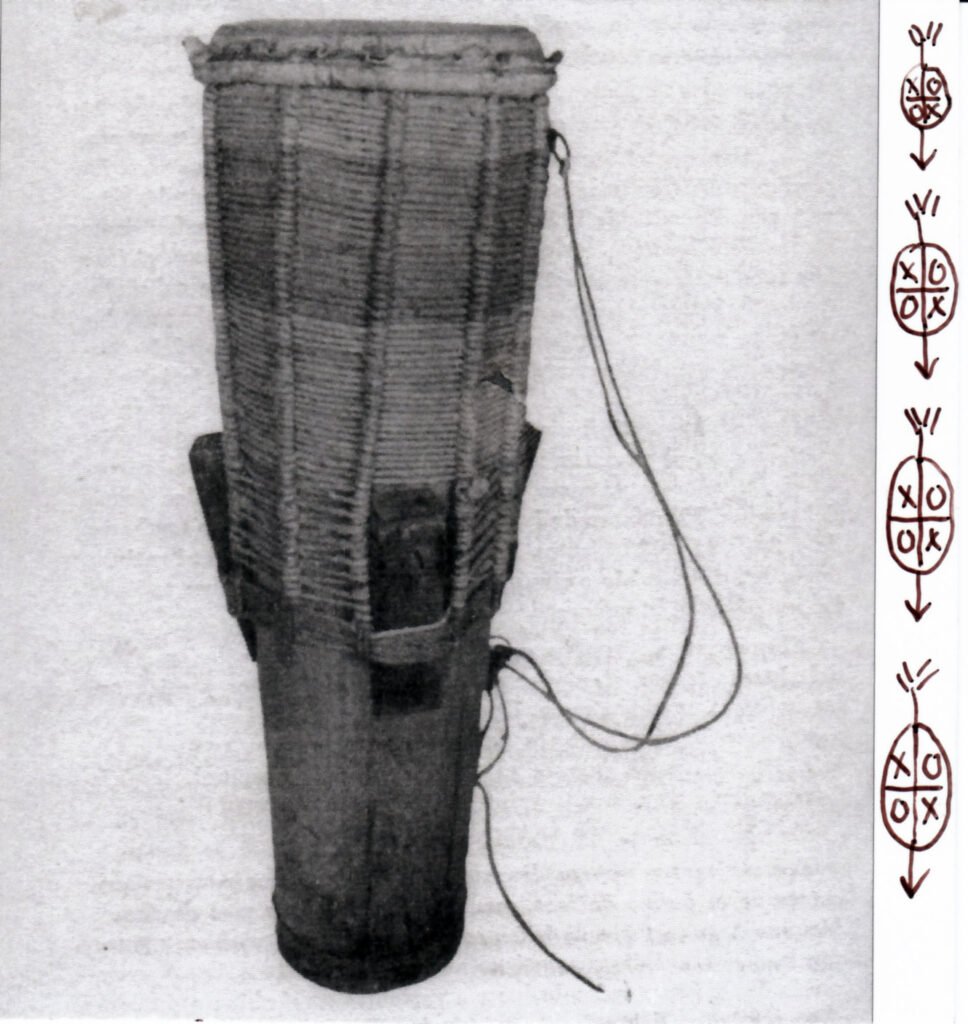

We recently completed restoration work on a Bonkó sent to us by a customer in Japan. This unique drum required extensive care and craftsmanship to bring it back to performance condition.

Manito meticulously:

Repaired numerous cracks in the shell

Resurfaced the bearing edge

Stripped and refinished the shell

Fabricated a new crown

Crafted custom side plates

Built a bottom ring from scratch

Custom bent new tuning lugs

To complete the restoration, I mounted a new steer skin head and documented the full process.

This Bonkó is now ready to sing again — a beautiful blend of traditional craftsmanship and modern precision.

The Bonkó Enchemiyá originates from the spiritual and cultural traditions of the Cross River region of southeastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroon. This area is home to the Efik, Efut, and Ibibio peoples, whose Ekpe (Leopard) societies played an essential role in governance, spirituality, and community cohesion. These societies used sacred drumming, masks, and initiatory rites to transmit moral teachings and ancestral knowledge.

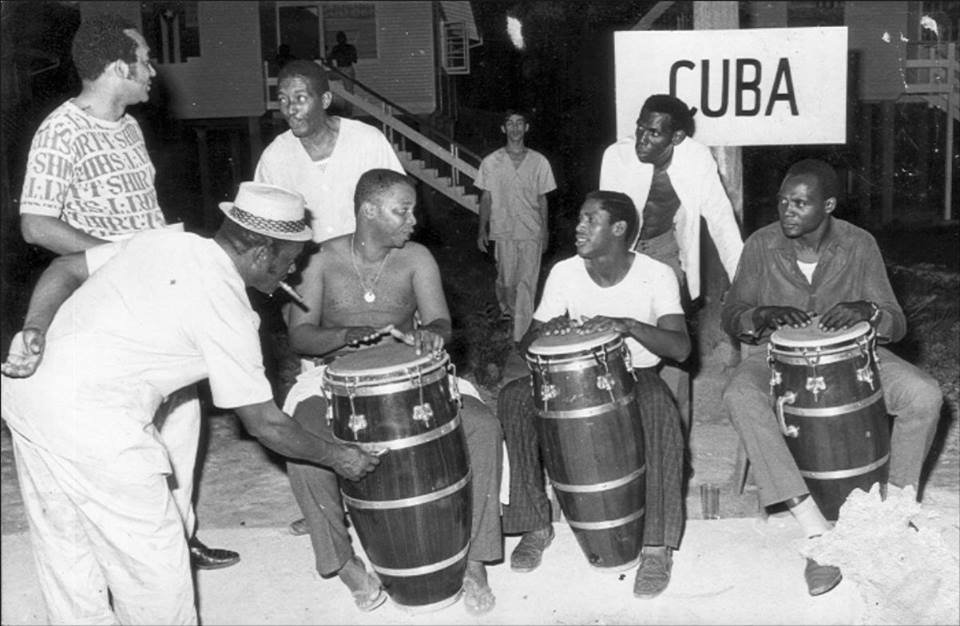

In the early 1800s, enslaved people from this region were forcibly brought to Cuba, primarily to Havana and Matanzas. Despite the trauma of enslavement and displacement, they preserved the spiritual frameworks of their ancestors by forming the Abakuá society—a mutual-aid and religious fraternity rooted in the structure of Ekpe, adapted to the colonial Cuban context.

The Bonkó Enchemiyá became the central instrument of this transplanted tradition—a drum that carried not only sound but cultural memory, sacred communication, and collective resistance.

The Bonkó Enchemiyá is the largest and most sacred of four drums in the biankomeko ensemble used in Abakuá ceremonies. This set includes:

These drums are hand-carved from wood, traditionally from sacred trees, and their heads are made from goat skin, tightened with ropes and wooden wedges. The drums are often marked with anaforuana, mystical symbols used within Abakuá cosmology.

The rhythms played on the Bonkó Enchemiyá are not merely musical—they are a codified language, intelligible only to initiated Abakuá members. The drum “speaks” in phrases that convey:

To outsiders, the patterns may seem abstract, but to insiders, they carry profound meaning, reinforcing social bonds, spiritual continuity, and a sense of shared identity that has endured for over two centuries.

The Bonkó Enchemiyá is used exclusively in Abakuá rituals, including:

The drum is considered alive in a spiritual sense. Before it is ever played, it must be ritually consecrated, “fed” with offerings, and imbued with sacred energy by elders. Drums that were used in historical ceremonies are treated with reverence; some are now housed in museums as sacred artifacts, not mere instruments.

During colonial rule, Spanish authorities often confiscated Abakuá drums and regalia, fearing the power and secrecy of the society. Despite repression, the Abakuá remained resilient, preserving its traditions through oral memory, symbolic language, and ritual performance.

While the Abakuá society remains closed to non-initiates and maintains a high level of secrecy, its musical influence has radiated outward, shaping major genres of Cuban music:

The Bonkó Enchemiyá, through its sound and spirit, has helped preserve African identity in Cuba, even as it has adapted to a changing world. It stands as a symbol of resistance, resilience, and rootedness in African heritage.

It is essential to approach Abakuá culture—and the Bonkó Enchemiyá in particular—with respect, humility, and understanding. These are not just musical expressions but living spiritual systems, maintained under conditions of historical violence and survival.

Outsiders are generally not permitted to participate in core Abakuá rituals, and the drums are sacred, not to be played or handled without initiation and training. However, the public manifestations of Abakuá music offer a glimpse into a world of deep ancestral intelligence and spiritual continuity.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Origins | Derived from West African Ekpe societies (Efik, Ibibio) via enslavement |

| Drum Ensemble | Biankomeko: Bonkó (lead) + Enkomó drums (Obiapá, Kuchi Yeremá, Binkomé) |

| Function | Sacred instrument; plays a coded language understood by initiates |

| Ceremonial Role | Used in initiations, funerals, masked dances, and spiritual rituals |

| Colonial Suppression | Drums and rituals were outlawed or seized; now preserved in some museums |

| Influence | Inspired rumba, Afro-Cuban jazz, and folkloric music |

| Spiritual Significance | Treated as sacred beings; drums are consecrated and ritually maintained |

We recently received this set of Gon Bops Mariano bongos from a customer for a custom upgrade — replacing the original heads with high-quality natural steer skin.

The setup:

7″ Macho: Mounted with 1mm steer skin

8.5″ Hembra: Mounted with 1.6mm steer skin

Each skin was soaked in cool water just until pliable to maintain integrity and achieve optimal tone. For the hembra, I used slightly longer mounting lugs to accommodate the thicker skin.

I used longer mounting lugs for the hembra to help draw the crown or rim down gradually, evenly and easily.

I also used a wooden jig to set the collar height at 3/16″. As the skin dried, I increased the collar height to 3/8″.

One interesting detail: these Gon Bops have relatively short crown ears, which makes for a tight fit between the flesh hoop, skin, and tuning hardware — something to keep in mind when reheading similar models.

Bongos—an iconic percussion instrument known for its bright, sharp tones and central role in Afro-Cuban and Latin American music—carries a rich history intertwined with cultural evolution, musical innovation, and craftsmanship. For those studying ethnomusicology and music, as well as master woodworkers interested in instrument construction, understanding the bongos’ origin, materials, and making process offers deeper insight into both its cultural and acoustic significance.

Bongos originated in eastern Cuba during the late 19th century, rooted in Afro-Cuban traditions influenced by Bantu and Yoruba peoples brought through the transatlantic slave trade. Initially, bongos served as communal instruments used in son and rumba styles, enabling intricate rhythmic dialogues that fueled dance and storytelling.

The instrument consists of two small, open-bottomed drums—the larger hembra (female) and smaller macho (male)—tied together, often played by a single percussionist using fingers and palms. Its construction, playing technique, and rhythmic vocabulary evolved alongside Cuban music, later spreading throughout Latin America and globally via salsa, Latin jazz, and world music.

Bongo drums are traditionally constructed using either stave or turned wood shell techniques, each offering distinct acoustic and aesthetic qualities.

For musicians and drum makers, understanding these construction methods is crucial in selecting or crafting bongos that meet desired tonal qualities, durability, and aesthetic preferences. Each material and method influences the instrument’s sound projection, sustain, timbre, and response to environmental factors.n in bongo making.

Wood choice profoundly influences the bongo’s tonal character, durability, and workability. Caribbean, South American, and North American woods each contribute distinct acoustic and aesthetic qualities.

| Wood Type | Region | Janka Hardness (lbs) | Density (g/cm³) | Tone Quality | Workability | Durability | Visual Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuban Mahogany | Caribbean (Cuba) | ~800 | ~0.55 | Warm, rich, mellow | Moderate (can be oily) | Moderate | Reddish-brown, fine grain, often with chatoyancy |

| Spanish Cedar | Caribbean | ~900 | ~0.50 | Warm, balanced, smooth | Easy to work, fragrant | Moderate | Reddish hue, aromatic, straight grain |

| Guayacan | Caribbean | ~4000 | ~1.05 | Bright, clear, articulate | Difficult due to hardness | Very durable | Dark brown with fine texture, oily finish |

| Kingwood | Caribbean | ~2200 | ~0.90 | Warm, resonant, complex | Difficult, brittle | Durable | Deep purples and browns, dense grain |

| Black Walnut | North America | ~1010 | ~0.64 | Warm, balanced, rich | Good, finishes well | Durable | Dark chocolate brown with purple undertones |

| Hard Maple | North America | ~1450 | ~0.70 | Bright, clear, focused tone | Hard but workable | Durable | Creamy white, sometimes with figured patterns |

| Ash | North America | ~1320 | ~0.66 | Bright, punchy, snappy | Easy to work | Durable | Pale with distinct grain, often straight |

| Poplar | North America | ~540 | ~0.42 | Balanced, warm, softer tone | Very easy to work | Moderate | Light brown with greenish or gray hues |

| Hickory | North America | ~1820 | ~0.82 | Bright, strong attack | Hard to work, tough | Very durable | Light to medium brown with prominent grain |

| Cherry | North America | ~950 | ~0.60 | Warm, mellow, rich | Good workability | Moderate | Reddish-brown, smooth grain |

| Santos Mahogany | South America | ~2200 | ~0.95 | Warm, rich, vibrant | Moderate to difficult | Durable | Deep reddish-brown with fine grain |

| Rosewood | South America | ~2200 | ~0.85 | Warm, complex, sustaining | Difficult, oily | Durable | Dark with rich streaking, oily finish |

Note: Janka hardness measures resistance to denting; higher numbers indicate harder woods, which generally support brighter tones and durability but require more skill to work.

Drumheads are vital for sound production, affecting tone, attack, sustain, and tuning stability.

| Head Type | Material | Tone Characteristics | Advantages | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Hide (Cow, Steerskin, Muleskin, Horse) | Animal skins (various) | Warm, bright, rich; varies by thickness and species | Traditional, warm tone, expressive dynamics | Highly sensitive to humidity and temperature; requires manual maintenance (oiling, occasional re-tensioning); less consistent across batches |

| Synthetic (Mylar, Kevlar, Fiberskyn) | Plastic or composite | Bright, focused, consistent tone | Weather-resistant, durable, easy to tune | Less complex tone; can sound harsh or metallic to some players |

Historically, natural hides were tensioned with tacks, heat, and later metal hardware. Today’s bongo makers often balance authenticity with practicality, selecting drumheads based on stylistic needs, climate, and maintenance considerations.

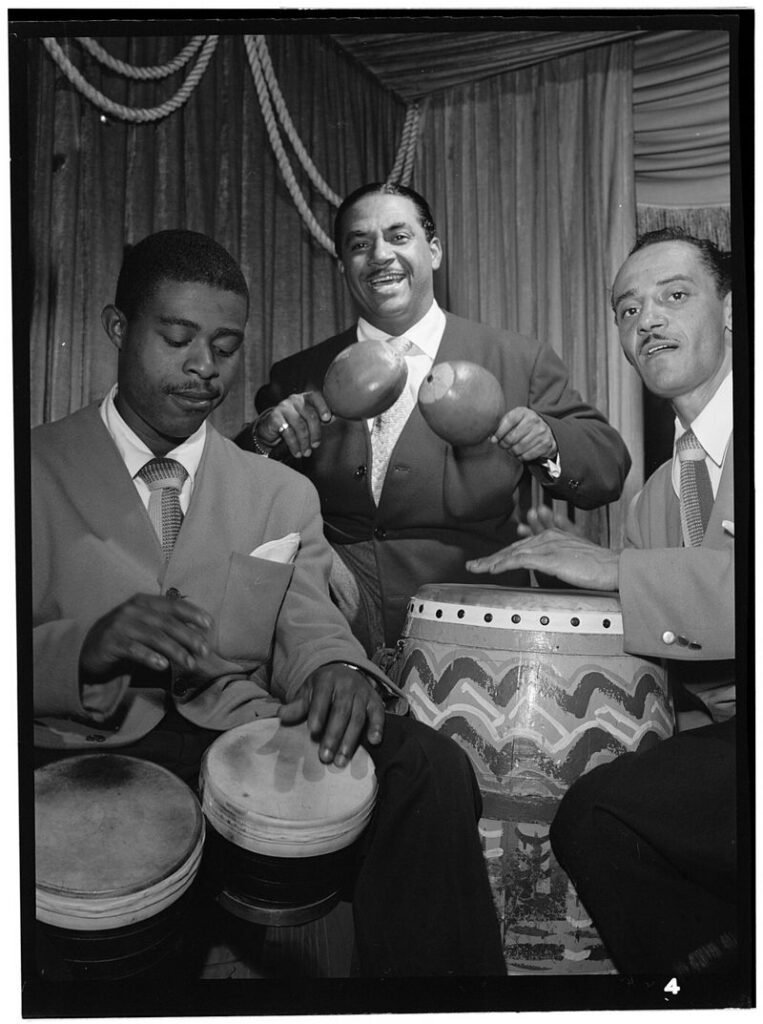

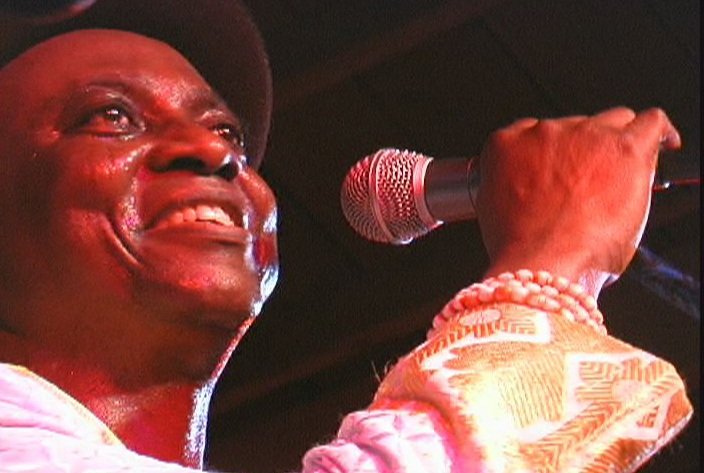

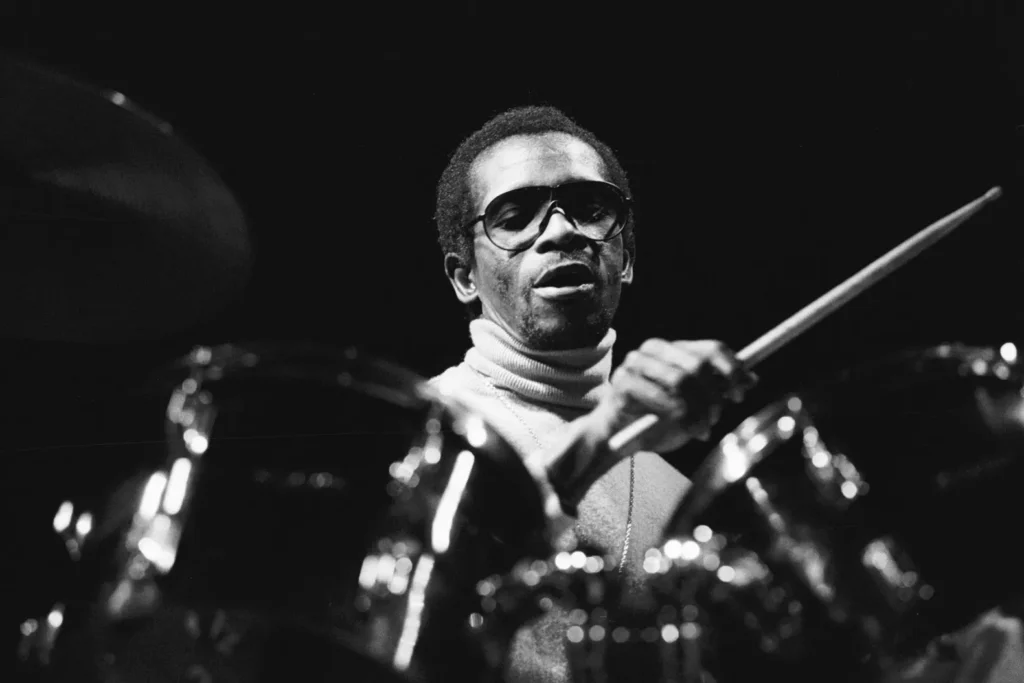

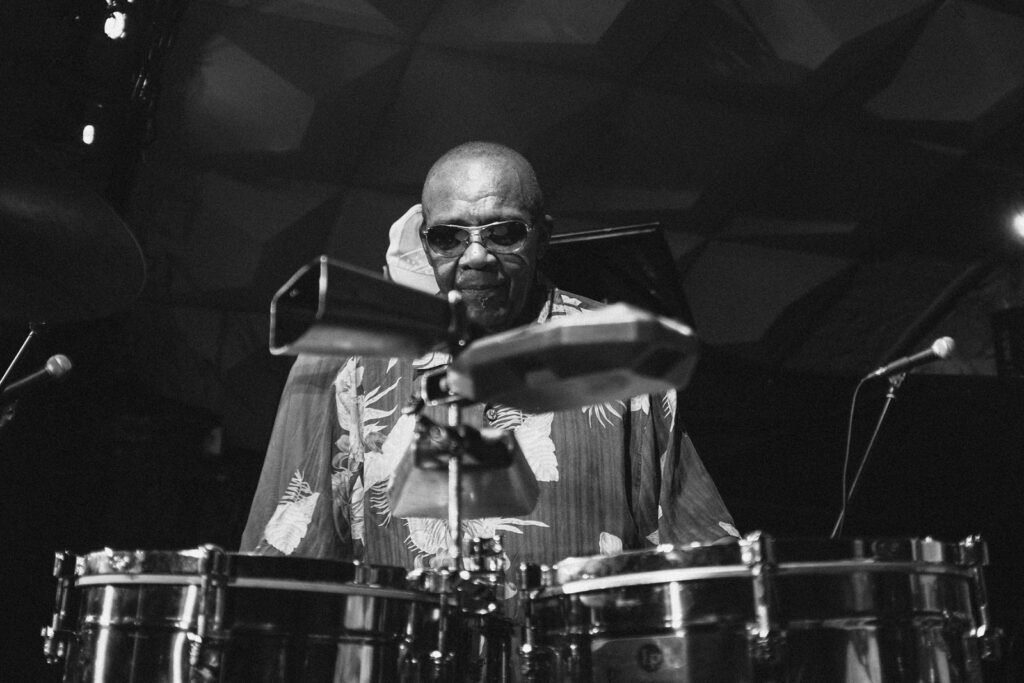

Understanding the players who shaped the bongo’s sound and cultural legacy deepens our appreciation of the instrument:

| Name | Contribution and Context |

|---|---|

| Guillermo “Papi” Oviedo | Laid foundational groundwork in Cuban son and rumba, preserving authentic rhythms that continue to inform bongo technique. |

| Antolín Suárez “Papa Kila” | Longtime bongosero for Arsenio Rodríguez’s orchestra, key in defining Afro-Cuban conjunto style. |

| Pedro Mena | Played with Conjunto Matamoros, top figure in early bongo performance. |

| Cándido Requena | Innovated tunable bongos, modernizing construction while dazzling audiences. |

| Rogelio Iglesias “Yeyo” | Central in Havana’s 1950s descarga scene, pushing improvisational boundaries. |

| Chicho Piquero | Virtuoso whose technique inspired Mongo Santamaría. |

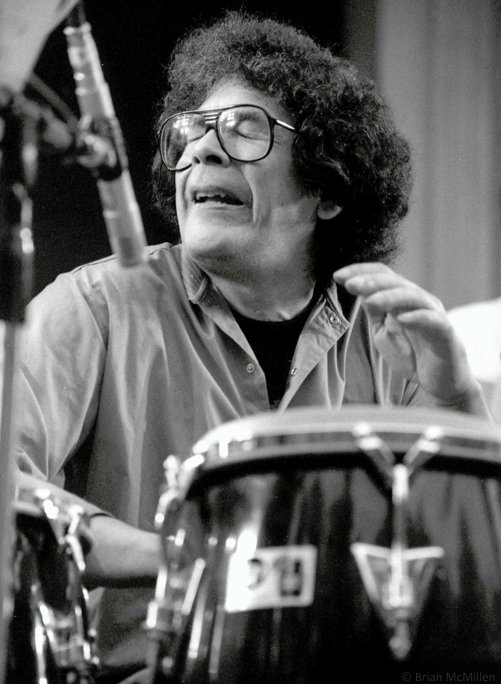

| Mongo Santamaría | International ambassador blending bongo and conga mastery across jazz, Latin, and popular music. |

| Armando Peraza | Brought blazing speed and style to jazz collaborations with legends like Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Santana. |

| Willie Bobo | Primarily a timbalero, also a skilled bongocero, collaborated with Tito Puente. |

| Tito Puente | Integrated bongos into Latin ensembles worldwide, popularizing the instrument. |

| Johnny “Dandy” Rodríguez | Iconic salsa figure known as a “bongo player’s bongo player,” influential in groove and precision. |

| Jack Costanzo “Mr. Bongo” | Credited with introducing bongos to American jazz audiences. |

| Changuito (José Luis Quintana) | Revolutionized salsa and timba drumming with innovative techniques. |

| Cándido Camero | Bridged Afro-Cuban percussion and jazz with remarkable fluidity. |

| Miguel “Angá” Díaz | Expanded expressive boundaries via folkloric rhythms and jazz fusion. |

| Ray Barretto & Julio “Julito” Collazo | Masters of Latin jazz percussion, enriched the bongo tradition. |

| Horacio “El Negro” Hernández & Roberto Quintero | Contemporary innovators pushing rhythmic and stylistic boundaries. |

Bongos embody a vibrant synthesis of Afro-Cuban culture, musical innovation, and skilled craftsmanship. Its journey—from Cuban barrios to global concert stages—reflects ongoing dialogues between tradition and modernity, musical expression and material mastery. For ethnomusicologists, musicians, and woodworkers alike, understanding the bongos’ cultural roots, construction techniques, wood properties, and influential players offers a rich, multidimensional perspective on this small but powerful instrument.

Whether crafting a set from carefully selected hardwoods or exploring its intricate rhythms, the bongo continues to inspire creativity and connection across cultures and generations.

Latin percussion bells are vital to genres such as Afro-Cuban rumba, salsa, samba, and beyond. Their journey—from traditional African rituals to contemporary global music—is a powerful testament to cultural adaptation, innovation, and enduring rhythm.

The origins of Latin percussion bells lie in West Africa, where iron bells were central to both music and spirituality. Among the most significant are the agogô, gankogui, and klama (also known as kanganu), each rooted in the cultural practices of distinct ethnic groups.

The agogô, from the Yoruba people of Nigeria, typically consists of one or two conjoined bells producing contrasting pitches. It was used in religious ceremonies to provide rhythmic structure and carry spiritual significance. In Ghana and Togo, the Ewe people developed the gankogui, a double bell with high and low tones. It serves as a timekeeper in Ewe drumming ensembles, anchoring complex polyrhythms.

The Fon people of Benin use the klama or kanganu—a single handheld iron bell—in Vodun (Voodoo) ceremonies. Like the gankogui, it maintains rhythm but also plays a spiritual role, marking transitions, summoning deities, and reinforcing chants with its sharp, resonant tone. Though less widely known outside Africa, it holds similar ritual and musical functions.

These bells were more than instruments; they were spiritual tools and cultural anchors. Through the transatlantic slave trade, their rhythmic and symbolic roles were carried to the Americas, where they became foundational to Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Latin musical traditions such as rumba, samba, and son.

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, the transatlantic slave trade forcibly uprooted millions of Africans, displacing them to various parts of the Americas. Along with them traveled a rich array of musical traditions, deeply embedded in communal life, spirituality, and cultural expression. Among these traditions, bell instruments—notably the agogô, gankogui, and various types of iron or wooden idiophones—played a crucial role in both rhythmic structure and spiritual signaling.

Despite the brutality and dehumanization of slavery, African musical practices proved resilient and adaptable, transforming and merging with local customs to form new syncretic genres and rituals across the Americas.

Early bells were typically hand-forged from iron or brass, often repurposed from recycled metals. Traditional designs included two bells connected by a handle, offering contrasting pitches used for timekeeping, polyrhythmic layering, and melodic phrasing.

Over time, bell designs adapted to meet new musical needs. Some evolved into multi-bell instruments, providing greater melodic variety. Others were redesigned for mounting on percussion racks or drum kits. The cowbell, originally an agricultural tool, was transformed into a key percussion instrument—especially in Cuban and Puerto Rican dance music.

Many early bells were hand-crafted by local blacksmiths using recycled materials. This artisanal tradition endures today, with makers producing instruments prized for their unique tone and cultural authenticity.

One of the most celebrated is JCR Percussion, founded by Cali Rivera in the Bronx. Rivera, originally from Puerto Rico, crafted bells, timbales, and bongos beloved by salsa and Afro-Cuban musicians for their warmth, clarity, and build quality. JCR instruments became iconic and remain sought after by serious percussionists.

Artisan-made bells often reflect regional identity and heritage, with forging techniques passed down through generations. Each bell is valued not only for its sound but also for its cultural lineage.

By the mid-20th century, companies like Latin Percussion (LP) began mass-producing bells. Founded in 1964 by Martin Cohen, LP made percussion bells accessible and consistent, crafting instruments from high-grade steel for performance and studio settings.

These industrial bells offered precise tuning, durable construction, and standardized sizing—ideal for professional musicians, touring acts, and schools.

| Feature | Artisanal Bells | Industrial Bells |

|---|---|---|

| Craft Method | Hand-forged from recycled metals | Machine-made from high-grade steel |

| Sound | Organic, warm, resonant | Bright, cutting, consistent |

| Cultural Significance | Rooted in tradition and ritual | Designed for stage and studio |

| Tuning | Tuned by ear | Precisely tuned and standardized |

| Availability | Limited, often niche | Widely available worldwide |

| Sustainability | Often eco-friendly | Less environmentally specific |

Bells often align with or complement the clave—the rhythmic foundation of much Afro-Latin music. In both sacred and secular contexts, bells guide dancers, signal transitions, and anchor ensemble timing.

In salsa and mambo, cowbells help drive the rhythm section, with timbaleros using multiple bells for dynamic contrast. In Latin jazz, bells contribute to layered polyrhythms and improvisation. In modern fusion, bells are integrated into electronic and global setups, continuing to evolve with technology.

From African rituals to New York salsa clubs, the Latin percussion bell has evolved into a dynamic and expressive instrument. Whether handcrafted by artisans or mass-produced for global stages, bells continue to anchor, drive, and color the music of the world—resonating with deep history and boundless creativity.

The conga drum—celebrated for its vibrant tone and dynamic rhythmic power—boasts a rich, multi-layered history rooted in Afro-Cuban traditions and shaped by centuries of cultural exchange and musical evolution.

Origins in Africa and Cuba

The origins of the conga drum trace back to West and Central Africa, particularly among the Bantu and Yoruba peoples. Instruments such as the makuta, yuka, and bembé drums were central to both ceremonial and social life in African communities. Through the transatlantic slave trade, these drumming traditions were carried to the Caribbean—especially Cuba—where enslaved Africans preserved their musical heritage through rhythm and ritual.

In Cuba, African drumming merged with indigenous and Spanish colonial musical influences, giving rise to uniquely Afro-Cuban styles. Early conga drums—known locally as tumbadoras—were often handcrafted from rum barrels and topped with animal skin heads, tuned by fire or moisture. These instruments played a key role in Afro-Cuban religious ceremonies and became essential to rumba, a rich, rhythm-driven genre that emerged in urban neighborhoods in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Evolution and Popularization

As Cuban music continued to develop throughout the 20th century, so did the conga’s role. No longer confined to ceremonial use, the drum became a driving force in popular dance music genres such as son cubano, mambo, and salsa.

During the 1930s and ’40s, the conga drum gained broader exposure, particularly in the United States, as Latin music began to cross over into the mainstream. Entertainers like Desi Arnaz introduced the “conga line” and brought the instrument to American television audiences, helping solidify its place in popular culture.

At the same time, Afro-Cuban rhythms began fusing with American jazz, giving rise to new hybrid styles like Latin jazz, and launching the conga on its journey to becoming a globally recognized instrument.

Modernization and Global Reach

By the mid-20th century, innovations in drum construction—particularly the introduction of mechanical tuning systems with metal lugs and rims—allowed for far greater control over pitch and tone. These technological advancements expanded the conga’s expressive range and opened the door for more intricate and melodic playing styles.

Legendary percussionists such as Chano Pozo, Mongo Santamaría, Tata Güines, Carlos “Patato” Valdés, Armando Peraza, Ray Barretto, and Giovanni Hidalgo played key roles in this evolution. Their groundbreaking work not only elevated the conga to an art form but also helped it transcend genre boundaries, blending Afro-Cuban rhythms with jazz, funk, and popular music worldwide.

The Conga in Contemporary Music

Today, the conga drum is a truly global instrument, embraced by musicians across cultures and genres. You’ll find congas in:

Latin Music: Salsa, rumba, mambo, timba, merengue

Jazz: Latin jazz, Afro-Cuban jazz, fusion jazz

Rock & Pop: Artists like Santana, The Rolling Stones, and countless modern acts

World & Fusion: Reggae, Afrobeat, funk, electronic, and hybrid world music styles

Conclusion

From its spiritual and communal roots in Africa to its starring role on international stages, the conga drum is more than just an instrument—it’s a symbol of cultural resilience, rhythmic innovation, and global connection. Its evolution mirrors the broader story of music as a unifying force across time, traditions, and continents.

Still today, every beat of the conga carries centuries of history, emotion, and soul—inviting players and listeners alike to connect through rhythm.

This Cuban Bonkó shell just arrived from Japan!

We’re gearing up for restoration and conversion: repairing cracks in the shell, resurfacing the bearing edge, fabricating a bottom rim, converting it to mechanical tuning, and mounting a steer skin head.

It’s definitely not your typical project — but that’s what makes it exciting. Looking forward to bringing this unique instrument back to life and seeing how it all comes together.

PreMounted™ Middle Eastern Steer Matched Set

For LP 11″, 11.75″ & 12.5″ Congas (EZ Curve Crowns Only)

The PreMounted™ Middle Eastern Steer Matched Set is expertly crafted with meticulous attention to tone, color, finish, and feel—offering a beautifully unified sound and look across your conga setup. Designed specifically to fit LP’s EZ Curve crown type, this set delivers premium performance for discerning players.

Specifications

Skin Type: Middle Eastern Steer

Skin Color: Amber

Crown Compatibility: EZ Curve

11″ Quinto Thickness: 1.8 mm

11.75″ Conga Thickness: 2.0 mm

12.5″ Tumba Thickness: 2.2 mm

Sound Characteristics

Crisp slaps

Round, open tones

Rich, full-bodied bass

Controlled overtones

Feel & Playability

Medium action

Smooth, responsive playing surface for both nuanced and powerful playing styles

Crown Compatibility Notice

This set is engineered specifically for LP’s EZ Curve crowns/rims, which feature a rim-radius curve and thinner gauge steel. It will not fit other LP crown styles, including:

Traditional: Rolled flat bar, thick gauge steel

Comfort Curve 1 (Soft Strike): Thick gauge steel, rim-radius curve

Comfort Curve 2 (X): Smooth ear, thick gauge steel, rim-radius curve

Extended Collar (Z): Extended collar with triangle-imprinted ear, shares dimensions with Top Tuning models