Bongos—an iconic percussion instrument known for its bright, sharp tones and central role in Afro-Cuban and Latin American music—carries a rich history intertwined with cultural evolution, musical innovation, and craftsmanship. For those studying ethnomusicology and music, as well as master woodworkers interested in instrument construction, understanding the bongos’ origin, materials, and making process offers deeper insight into both its cultural and acoustic significance.

Origins and Cultural Context

Bongos originated in eastern Cuba during the late 19th century, rooted in Afro-Cuban traditions influenced by Bantu and Yoruba peoples brought through the transatlantic slave trade. Initially, bongos served as communal instruments used in son and rumba styles, enabling intricate rhythmic dialogues that fueled dance and storytelling.

The instrument consists of two small, open-bottomed drums—the larger hembra (female) and smaller macho (male)—tied together, often played by a single percussionist using fingers and palms. Its construction, playing technique, and rhythmic vocabulary evolved alongside Cuban music, later spreading throughout Latin America and globally via salsa, Latin jazz, and world music.

Bongo Shell Construction: Stave, Turned, and Fiberglass

Bongo drums are traditionally constructed using either stave or turned wood shell techniques, each offering distinct acoustic and aesthetic qualities.

- Stave Construction involves assembling vertical wooden slats (staves) glued and pressed together to form the drum shell. This method allows for precise control over shell thickness and shape, contributing to a warm, resonant tone favored in traditional Latin percussion.

- Turned Construction uses a solid block of wood that is lathed on a wood-turning lathe, resulting in a seamless, smooth shell with consistent thickness. This technique often enhances projection and sustain while maintaining the natural wood character.

- Fiberglass Construction represents a modern approach, where shells are molded from composite fiberglass materials. Fiberglass bongos offer increased durability and resistance to environmental changes such as humidity and temperature fluctuations. Additionally, fiberglass shells tend to produce a brighter, more cutting tone with consistent sound quality over time. They are lighter than some wooden shells and can be designed in a variety of shapes and finishes.

For musicians and drum makers, understanding these construction methods is crucial in selecting or crafting bongos that meet desired tonal qualities, durability, and aesthetic preferences. Each material and method influences the instrument’s sound projection, sustain, timbre, and response to environmental factors.n in bongo making.

Wood Selection and Properties: Caribbean, South American, and North American Woods

Wood choice profoundly influences the bongo’s tonal character, durability, and workability. Caribbean, South American, and North American woods each contribute distinct acoustic and aesthetic qualities.

| Wood Type | Region | Janka Hardness (lbs) | Density (g/cm³) | Tone Quality | Workability | Durability | Visual Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuban Mahogany | Caribbean (Cuba) | ~800 | ~0.55 | Warm, rich, mellow | Moderate (can be oily) | Moderate | Reddish-brown, fine grain, often with chatoyancy |

| Spanish Cedar | Caribbean | ~900 | ~0.50 | Warm, balanced, smooth | Easy to work, fragrant | Moderate | Reddish hue, aromatic, straight grain |

| Guayacan | Caribbean | ~4000 | ~1.05 | Bright, clear, articulate | Difficult due to hardness | Very durable | Dark brown with fine texture, oily finish |

| Kingwood | Caribbean | ~2200 | ~0.90 | Warm, resonant, complex | Difficult, brittle | Durable | Deep purples and browns, dense grain |

| Black Walnut | North America | ~1010 | ~0.64 | Warm, balanced, rich | Good, finishes well | Durable | Dark chocolate brown with purple undertones |

| Hard Maple | North America | ~1450 | ~0.70 | Bright, clear, focused tone | Hard but workable | Durable | Creamy white, sometimes with figured patterns |

| Ash | North America | ~1320 | ~0.66 | Bright, punchy, snappy | Easy to work | Durable | Pale with distinct grain, often straight |

| Poplar | North America | ~540 | ~0.42 | Balanced, warm, softer tone | Very easy to work | Moderate | Light brown with greenish or gray hues |

| Hickory | North America | ~1820 | ~0.82 | Bright, strong attack | Hard to work, tough | Very durable | Light to medium brown with prominent grain |

| Cherry | North America | ~950 | ~0.60 | Warm, mellow, rich | Good workability | Moderate | Reddish-brown, smooth grain |

| Santos Mahogany | South America | ~2200 | ~0.95 | Warm, rich, vibrant | Moderate to difficult | Durable | Deep reddish-brown with fine grain |

| Rosewood | South America | ~2200 | ~0.85 | Warm, complex, sustaining | Difficult, oily | Durable | Dark with rich streaking, oily finish |

Note: Janka hardness measures resistance to denting; higher numbers indicate harder woods, which generally support brighter tones and durability but require more skill to work.

Drumheads: Materials and Tonal Impact

Drumheads are vital for sound production, affecting tone, attack, sustain, and tuning stability.

| Head Type | Material | Tone Characteristics | Advantages | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Hide (Cow, Steerskin, Muleskin, Horse) | Animal skins (various) | Warm, bright, rich; varies by thickness and species | Traditional, warm tone, expressive dynamics | Highly sensitive to humidity and temperature; requires manual maintenance (oiling, occasional re-tensioning); less consistent across batches |

| Synthetic (Mylar, Kevlar, Fiberskyn) | Plastic or composite | Bright, focused, consistent tone | Weather-resistant, durable, easy to tune | Less complex tone; can sound harsh or metallic to some players |

Historically, natural hides were tensioned with tacks, heat, and later metal hardware. Today’s bongo makers often balance authenticity with practicality, selecting drumheads based on stylistic needs, climate, and maintenance considerations.

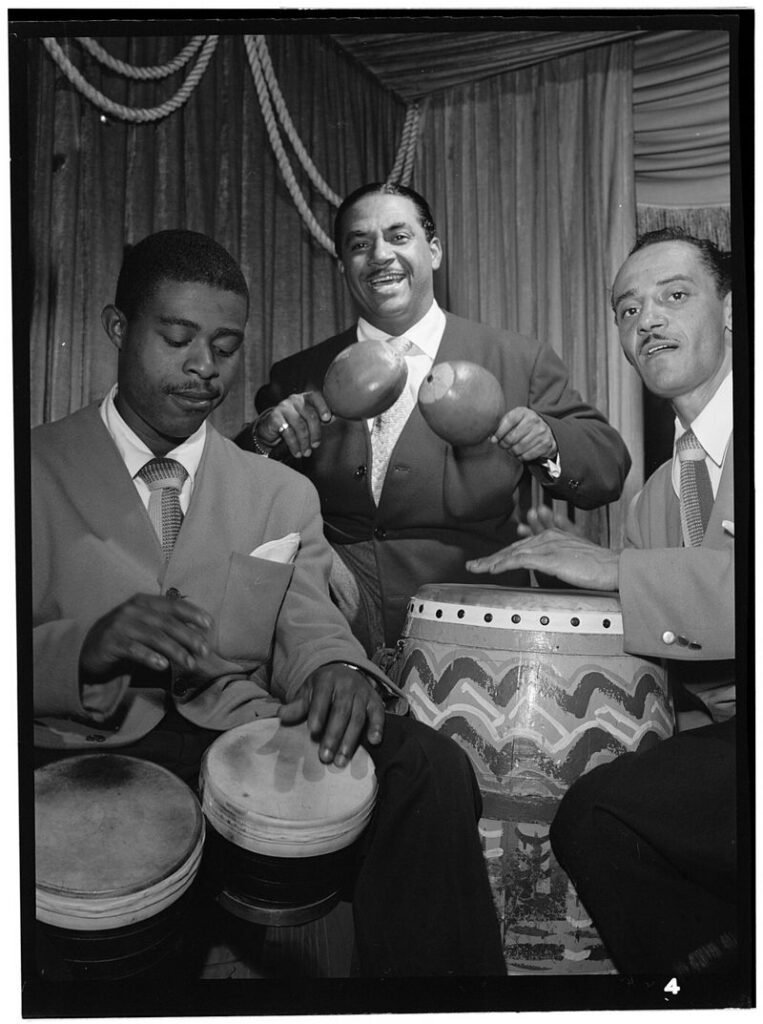

Influential and Popular Bongoceros

Understanding the players who shaped the bongo’s sound and cultural legacy deepens our appreciation of the instrument:

| Name | Contribution and Context |

|---|---|

| Guillermo “Papi” Oviedo | Laid foundational groundwork in Cuban son and rumba, preserving authentic rhythms that continue to inform bongo technique. |

| Antolín Suárez “Papa Kila” | Longtime bongosero for Arsenio Rodríguez’s orchestra, key in defining Afro-Cuban conjunto style. |

| Pedro Mena | Played with Conjunto Matamoros, top figure in early bongo performance. |

| Cándido Requena | Innovated tunable bongos, modernizing construction while dazzling audiences. |

| Rogelio Iglesias “Yeyo” | Central in Havana’s 1950s descarga scene, pushing improvisational boundaries. |

| Chicho Piquero | Virtuoso whose technique inspired Mongo Santamaría. |

| Mongo Santamaría | International ambassador blending bongo and conga mastery across jazz, Latin, and popular music. |

| Armando Peraza | Brought blazing speed and style to jazz collaborations with legends like Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Santana. |

| Willie Bobo | Primarily a timbalero, also a skilled bongocero, collaborated with Tito Puente. |

| Tito Puente | Integrated bongos into Latin ensembles worldwide, popularizing the instrument. |

| Johnny “Dandy” Rodríguez | Iconic salsa figure known as a “bongo player’s bongo player,” influential in groove and precision. |

| Jack Costanzo “Mr. Bongo” | Credited with introducing bongos to American jazz audiences. |

| Changuito (José Luis Quintana) | Revolutionized salsa and timba drumming with innovative techniques. |

| Cándido Camero | Bridged Afro-Cuban percussion and jazz with remarkable fluidity. |

| Miguel “Angá” Díaz | Expanded expressive boundaries via folkloric rhythms and jazz fusion. |

| Ray Barretto & Julio “Julito” Collazo | Masters of Latin jazz percussion, enriched the bongo tradition. |

| Horacio “El Negro” Hernández & Roberto Quintero | Contemporary innovators pushing rhythmic and stylistic boundaries. |

Conclusion

Bongos embody a vibrant synthesis of Afro-Cuban culture, musical innovation, and skilled craftsmanship. Its journey—from Cuban barrios to global concert stages—reflects ongoing dialogues between tradition and modernity, musical expression and material mastery. For ethnomusicologists, musicians, and woodworkers alike, understanding the bongos’ cultural roots, construction techniques, wood properties, and influential players offers a rich, multidimensional perspective on this small but powerful instrument.

Whether crafting a set from carefully selected hardwoods or exploring its intricate rhythms, the bongo continues to inspire creativity and connection across cultures and generations.